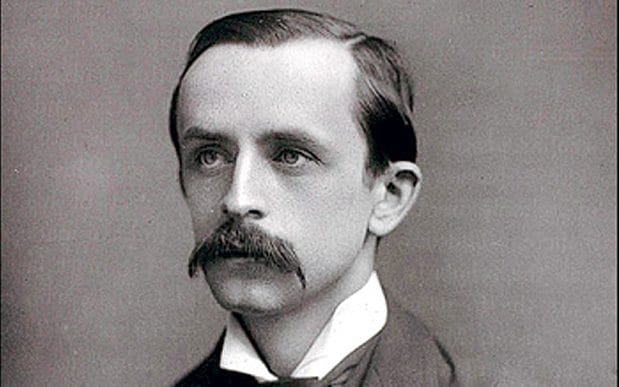

James Matthew Barrie was born in Scotland on May 9, 1860 to working-class parents, the ninth child of ten, two of whom died before he was born. Barrie’s brother, David, died in an ice skating accident two days before his fourteenth birthday when Barrie was six years old.

David had always been his mother’s favorite and with his death she became deeply depressed. However, she derived some comfort knowing that David would stay a boy forever—he would never grow up, nor would he ever leave her. In his biographical book about his mother, Margaret Ogilvy, Barrie describes a night after his brother’s death when his older sister urged him to go to their mother and tell her that she still had another boy.

“…but the room was dark, and when I heard the door shut and no sound come from the bed I was afraid, and I stood still…after a while I heard a listless voice that had never been listless before say, ‘Is that you?’ I think the tone hurt me, for I made no answer, and then the voice said more anxiously, ‘Is that you?’ again. I thought it was the dead boy she was speaking to, and I said in a little lonely voice, ‘No, it’s no him, it’s just me.’ Then I heard a cry, and my mother turned in bed, and though it was dark I knew that she was holding out her arms.” 13

After that night, Barrie sat with his mother night after night in her bedroom, trying to make her forget his deceased brother. As a result, Barrie was an insomniac for the rest of his life. To take his brother’s place and gain his mother’s favor, Barrie dressed up in David’s clothes and learned how to whistle the way he did. When Barrie turned fourteen, (the same age as David when he died), he stopped growing at only about five feet tall! The ties between mother and son strengthened over the years, but there would be a price to pay for their unusual bond.

Although his parents wanted him to go into the ministry (perhaps because this is what they wanted for David) Barrie had other ideas. As a teenager, he developed an interest in literature and the theatre. After university, Barrie pursued a career as a reporter and freelance writer. He had much success as an author of books and plays.

Barrie married actress Mary Ansell although he questioned his attractiveness and masculinity. But purportedly, he was impotent, and declined to have sexual relations with his wife, remarking, “Boys can’t love.” The couple divorced after Mary had an affair.

Barrie traveled in high literary circles and had many famous friends. He had a long correspondence with Robert Louis Stevenson. He befriended Antarctica explorer Robert Scott and was the godfather to Scott’s son, Peter. He was asked by Scott to take care of his wife and son while he was on his expedition to the South Pole. Barrie was so proud of Scott’s letter to him that he carried it with him for the rest of his life.

It’s said that Barrie’s mother read the stories of Robert Lewis Stevenson, stories of adventures and pirates. She inspired the character of Wendy. At eight years of age, Margaret lost her own mother and had to take over the role of mistress of the house and mother to her younger brother—much as Wendy does for the “lost boys.”

David was never far from his mind. The last play Barrie wrote was The Boy David based on the Biblical story of King Saul and a young David. Barrie also published a novel, The Little White Bird, which tells the story of a bachelor who befriends the boy, David. On walks through Kensington Gardens, he tells David about Peter Pan who appears at night in the Gardens. The play Peter Pan was produced in 1904 and the book, Peter and Wendy, was published a few years later. Apparently, Peter Pan took shape through the stories Barrie told to the sons of his dear friend, Sylvia Llewelyn Davies.

Childless himself, Barrie became the guardian of these five boys after both of their parents died of cancer. Eventually, he adopted the boys and they became his family—“the lost boys.” Sadly, death befell three of the boys as adults. In 1937, Barrie died at seventy-seven.

Barrie assumed the role of the replacement child for his mother following his brother’s death. In his younger years, Barrie’s job in life was to make his mother happy—to be her companion, to entertain and to heal her. Having achieved fame and wealth, his mission in later life was to take care of children. Ultimately, he sacrificed a more intimate personal life for others.

This month’s profile is excerpted with permission from Replacement Children: The Unconscious Script, by Rita Battat and Dr. Abigail Brenner.