You can become your unique self!

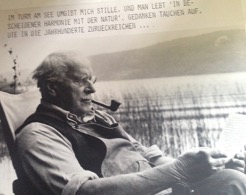

This is the message of world-famous psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961). Jung was a replacement child.

His life and work show us how one can find one’s way out of the “dilemma” (Porot) of being a replacement child. His concept of the “individuation process” offers hope to all human beings who may feel alienated from themselves and who seek a way to reconnect with their “true self”, their “creative self” (Winnicott). It entails becoming conscious of what one may not have known, looking for what may be hidden causes of one’s feeling ill at ease in life.

Carl Gustav Jung was born on 26 July 1875, two years after his brother died after living only five days. His parents also previously mourned two stillborn girls. Can you imagine how his mother Emilie felt at 27 years old, after having lost three children? Or his father Paul, a pastor whose first-born son was named for him and lost?

Carl Gustav survived. He studied medicine and worked as a psychiatrist and university professor before he founded what is today known as depth psychology or Analytical Psychology. He was married with Emma Rauschenbach and the couple had five healthy children. Jung died at the age of 86 years old, on 6 June 1961, sixty years ago. Jung is likely to have known of the missing siblings but he never used the term ‘replacement child.’ That complex syndrome with its attending symptoms of survivor’s guilt, protracted grief and relational challenges had not yet been defined. The first reference article by Cain & Cain appeared only in 1964 (read the full article here).

As a child, Jung suffered from eczema, nightmares and morbid preoccupations (Kutek). He had difficulties in school and looked to some like a lonely kind of boy. When he was only seven years old, Jung found a stone, ‘his stone’, as we read in his autobiography. He asked himself am I it, or is it I? “Am I the one who is sitting on the stone, or am I the stone on which he is sitting?” (Memories, Dreams and Reflections (MDR), p. 20).

Such early questioning with respect to one’s existence can be a hallmark sign of replacement children; they are born into a family stricken by grief and can be unconsciously given the role to make up for a lost child or other family member, or even equally unconsciously self-identify with such a role, out of longing for the lost one.

Was Jung struggling to find his own identity amidst the “ghosts in the nursery”? Such a presence was noticed by psychoanalysts in some families under such circumstances (Faimberg, Cramer). We can understand Jung’s questioning. A replacement child may think or feel: “why am I here and the other is not?” or “If the other would not have died, would I have been conceived and born?”

In Jung’s own words: “It seemed to me miraculous that I should not have been prematurely annihilated” (MDR, p. 4). He also referred to “an unconscious suicidal urge, or . . . a fatal resistance to life in this world,” in his early years. (MDR, p. 9) Also later, as a 15-year old schoolboy he asked himself again: “What is my notion of self, and who is the other?” “Am I the other or is the other in me?”

Whether at a young age or later in life, replacement children can struggle with their sense of identity and their feeling of self-worth, they may grapple with the big questions of life and death, and they can find it hard to find fulfilling relationships. Some even ignore that they are a replacement child because they were never told; some have a negative bonding experience with their mother, others feel they do not measure up in father’s eyes. In Jung’s case, he felt closer to his mother than to his father. When he was three, his mother spent some time away, in a sanatorium because she was depressed, this can feel like an abandonment to a young child. Jung also recalled that the atmosphere in the house had become “unbreathable”. In some families that are traumatized by a tragic loss, there is suffering from frozen grief or depression, or a lack of communication; some parents even separate due to their heart-break.

“Is there anything more fundamental than the realization, ‘This is what I am’?”

This is the central question Carl Gustav Jung, the founder of Analytical Psychology, asked himself and the answers he gives in his collected works are an invaluable help for those who seek an answer to their most fundamental questions:

Who am I?

What is the meaning of my life?

How can I fully live my life?

How can I best love myself and others?

His grandson Andreas Jung, pays respect to his grandfather: “He researched the human soul and his goal was the Self.” (Andreas Jung, 2011) Jung’s passion and his plea was for human beings to seek more consciousness, to engage in an awareness-raising process throughout their lives. For replacement children, such consciousness-raising can bring to an end the potential confusion between the living and the deceased sibling.

“…the self is our life’s goal, for it is the completest expression of that fateful combination we call individuality” (CW 7, §404), this is a most hopeful prospect: because of the circumstances surrounding their coming into being, adult replacement children can find a deeper, more meaningful access to their existence. Their suffering may prompt them to examine their life and even to seek counselling. This can bring them to the most important discovery that within themselves there is dormant the memory of their true original self and that they can reconnect with it. This is akin to what Jung called a “psychological rebirth” (CW 9i). Nothing too mystical or metaphysical, but rebirth as a “psychic reality”; it is simply the realization of the inalienable kernel to one’s existence, which Jung called the self, an archetypal given, allowing for “the striving after your own being” (MDR, p. 382), a continuous process of improvement and renewal.

Jung knew his share of struggles; he once referred to the “individuation process” as the sum of all detours and wrong turns taken in one’s life. Don’t we all know such detours? Yet according to Jung, the individuation process has an innate directional purpose aiming at self-realization and is achieved by a life-long dialogue with the images in one’s unconscious. Jung looked for what was centrally important to his life and found words to describe what today is helping many people, around the world.

Looking at life in a deeper way, paying attention to our day-dreams and the dreams at night, connecting our feeling and thinking, honoring our intuition and our senses, finding out what was our place and role in the family, and what projections may have come to bear on us or what projections we ourselves might have, is part of this process.

Carl Gustav Jung became a wise old man; in daily parlance, we use today many terms coined by him, such as the individuation process, complexes as the building stones of the psyche, the concept of extroversion and introversion, of the collective unconscious, the archetypal Self, Anima and Animus and other archetypes, innate patterns informing our existence, and the psychological types assessed in the Myers-Briggs-Test.

Jung referred to the self-healing quality of psyche, to the dynamic which seeks our self-realization. He wrote: “My life is a story of the self-realization of the unconscious” (MDR, p. 3). He saw it as vital to differentiate oneself from projections and unconscious influences, illusions and self-delusions, and to discover one’s very own individual, unique self.

That way, we develop our personality and contribute as conscious individuals the best we can offer to our loved-ones, families and to society.

What better invitation for an adult replacement child than this:

feel comfortable with your true self – be at one with yourself!

Kristina Schellinski is a Co-Founder of the Replacement Child Forum and Author of Individuation for Adult Replacement Children